Colie Wertz is a concept artist and modeler whose career has taken him cross-country from Clemson University in South Carolina to working with the biggest studios on the west coast. In the years since he’s started down the path of a “generalist” visual effect artist, he’s accumulated experience and is credited in a long list of science fiction movies. Star Wars first sparked his creative interest and it shows in the laser focus of his portfolio, with lovingly crafted mechanical droids and spaceships, all of which portray leaps and bounds beyond the capabilities of modern tech. Here, he tells us more about his evolution as an artist and how KeyShot has helped shape his path.

What sparked your interest in becoming a 3D Concept Artist?

My interest in becoming a Concept Artist has been quite a journey, no doubt sparked by seeing the work created by Ralph McQuarrie and Joe Jonston for Star Wars when I was a kid. It was so well planned out, and I believed it.

For starters, I’ve drawn all my life. I have an architectural degree, and that came with a lot of practical modeling and drawing. I got into the VFX industry as a generalist using a Mac and some (somewhat) affordable software in ’98. Non-industry pipeline stuff. I got pigeon-holed as a CG modeler eventually, and it paid the bills. The generalist approach to doing shots, though, had me interested in trying to combine all my visual skills once I learned enough 3D and could find a financial intersection between hardware, software, and the demand for my work.

What was the turning point in your career?

The turning point in my career was a few-fold. Dropping architecture and moving across the country (I’m from SC, moved to LA) was a big one. Packed the car, and drove to Hollywood. There were no schools, no internet tuts at that time. It was the wild west. You just had to learn, somehow. SiliconGraphics machines were expensive and complex (UNIX) and if you weren’t at a school that had them, being competitive in VFX was tough. But things happen.

The second big move was getting hired at ILM, where I really spread my generalist wings. I was in a little boutique group there, doing shots out of the pipeline on Macs. And I was around those SiliconGraphics machines I’d once thought were unattainable to sit in front of. The Mac boutique lasted a few years and, eventually, the group was disbanded as the pipeline was just too, well, industrial. A Mack truck approach.

I was, however, located next to the Art Department and got a really good education on how they worked as a group and as individuals, as well as their styles. I realized that all the art being produced there was a way to communicate an idea more clearly for someone either up or down the production line to better realize the director’s ideas for his/her finished product. That tied in directly to my architecture…my construction drawings in architecture were for the builders, etc. It was the same in CG and Concept Art for me. In the end, the deliverable was 2D, either seen on paper or a screen. The quality of communication is the art or the illustration.

I was beginning to see the “cost of entry” into the CG world drop about 12 years into ILM. As software improved, more players got involved in the market, and PC’s were less expensive and more powerful than Macs. SGI’s were unnecessary. I left ILM and tried to put myself in more design-oriented positions at different companies near where I lived. Schools had started CG programs and the number of people competing in the CG market grew exponentially, driving pay and open slots down.

It was an important point as I saw my design interest setting me apart from someone years younger, fresh out of school, hungry to work for less at a prestigious facility. I understood as that person was me at an earlier part of my career, driving across the country. I had a hunger for learning and studying more concept art, so I did. I had the technical knowledge and experience of a pipeline and non-pipeline generalist and decided to leverage that to give myself opportunities in what I always hoped for, which was a Concept Art career. With the intersection of affordability, confidence in my skills, and more info online, I could attack this goal. I still work hard at that goal. It has many facets, I’m finding!

What is unique about your approach to a project?

What makes my approach a little different than other artists is my passion for drawing. People don’t seem to draw as much as they used to. I guess it’s a by-product of modeling scenes. It makes sense in some ways, but a sketch can get things rolling fast, and I just love it. Gimme a pencil and paper.

But when I don’t have that around or am just standing around in a coffee line, I use a number of programs on my iPhone and iPad to sketch ideas whenever I want, whenever the mood strikes. I can doodle a sketch on a napkin and take a picture of it, then paint over it. It’s mind-boggling to me that this is possible, but it is.

Because I was groomed in CG modeling for so many years, I know what a modeler needs to get a good model started, and I sketch that way. I ask myself “could you get this model started?” as I sketch. So I know how far to take a sketch. Colors, paint jobs, mood, etc., can get going on a phone now. Not a $10k machine, sitting at a desk.

What is your primary 3D modeling software?

My primary modeling software is Maya. ILM used it in their pipeline for StarWars: Episode 1 and I made the switch around that time from Alias for surfacing and FormZ for details. Maya gave me both polys and NURBS, and the ability to render both in a scene. It was my first “all-in-one” experience, and I worked hard to put myself in positions to embrace all the aspects that Maya has to offer. Was I an evangelist? Maybe, but back then, you needed to be on what everyone was using so files could be useful to someone other than you.

That’s not the case today. Everything plays nicely together, and you can make a good model work in most renderers. I was taught the best ways to model for efficient pipeline use at ILM, and continue a lot of those even in Concept Art, to keep the models viable down the line in CG, should the show need it. Not always, but I try! I use MOI, Gravity Sketch, and ZBrush, too. Whatever the job calls for.

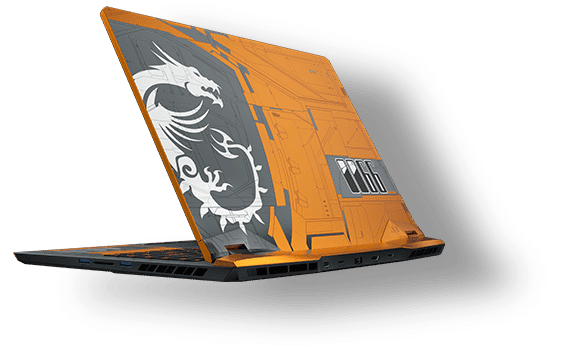

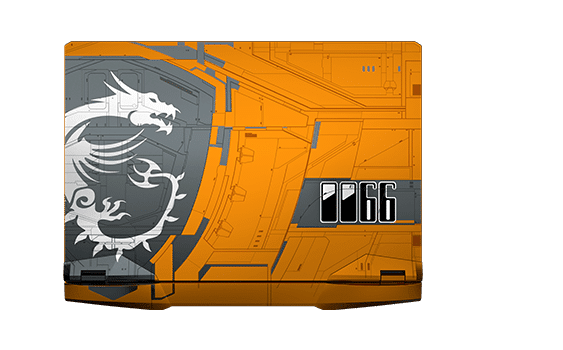

GE66 Raider Dragonshield Limited Edition

MSI, in collaboration with Colie Wertz, will release the Limited Edition GE66 Raider Dragonshield high-powered laptop. The laptop features Colie’s familiar style based on the Dragonshield concept ship design created exclusively for MSI. With an Intel Core i7, 64GB RAM, 2TB SSD, and NVIDIA’s GeForce RTX 2080, this 15.6″ laptop with backlit keyboard, USB-C, and Windows 10 will bring you some of the best GPU rendering available.

Learn more at MSI >>

Where in the process do you use KeyShot?

I employ KeyShot early in my design process. I bang out a model in whatever, then get it into KeyShot to look at it with fast materials and lighting. I may take a pic of my screen with my phone as I’m running out the door so I can start painting over it. If I have a little more time, I may run out a bunch of passes and paint/reveal them in Photoshop. KeyShot’s been there for me for almost a decade now. Its ability to handle large polycounts is huge.

What makes KeyShot an important tool to have?

KeyShot is an indispensable tool for me now, as I’ve gotten to know the Material Graph. The Labels allow me to add graphics to a non-UV’d model in a heartbeat and adjust their size, as well as mix them with degrees of weathering on the fly. It’s a big deal for me as, at any moment, I can spit out a super-high quality render of a model I haven’t had to burn time UV’ing. Its materials are, and have always been, easy to understand and use. It was the first “let us worry about the shaders” experience I ever had, and it blew me away.

What advice would you give to someone interested in doing what you do?

The advice I’d give someone interested in doing what I do would be to study the world around you, any chance you get. Look at the dirt on your car. Take a picture of it in different light and angles. Chances are, you can replicate it in a good renderer like KeyShot. A little test might come in handy later down the road. Study forms. Cars are great for this. Educate yourself on art and architectural styles of the past. Get better at drawing. Every sketch I do I try to get a little better or communicate something I haven’t before. Find the intersection of the parts of your career that will enable you to move forward, and make that a goal.